Labor Market Strength Is No Justification for a Recession

January 13, 2023

By Justin Bloesch, Mike Konczal

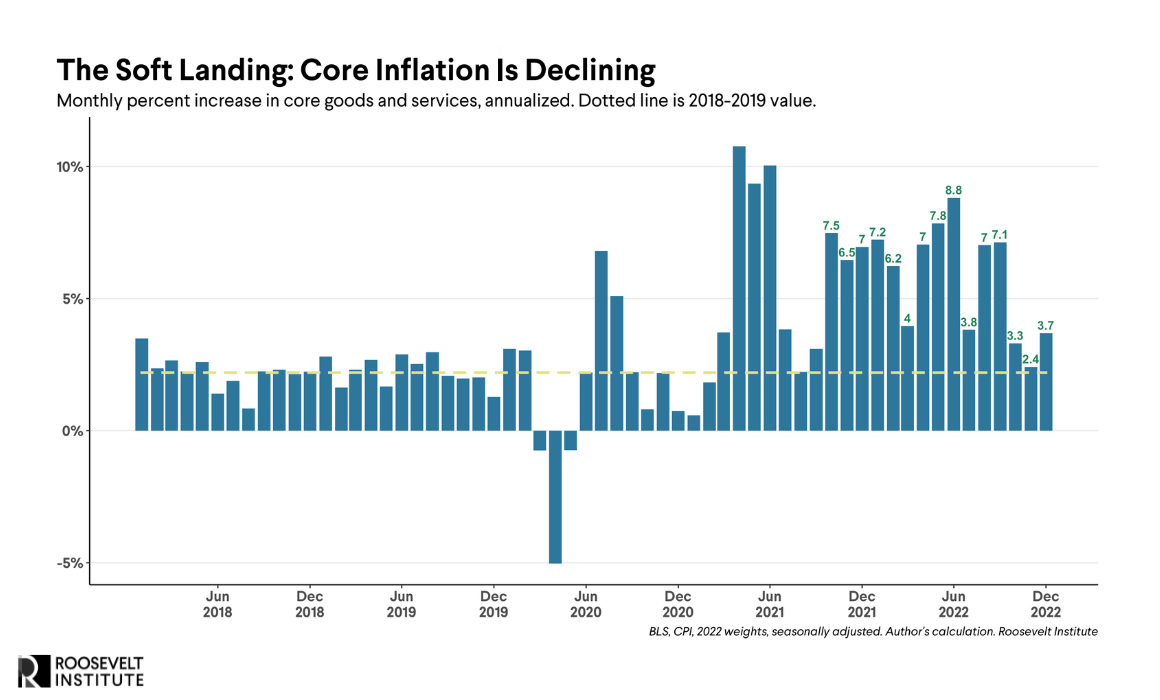

Inflation is finally returning to trend. Over the past three months, Consumer Price Index (CPI) core inflation was 3.1 percent, less than half of the range we saw in early 2022. Longer-term measures are also now declining. With core inflation normalizing, the Federal Reserve will likely use labor market data to justify a continued hawkish position. However, the labor market is already cooling to a level that is strong but not inflationary. With patience, the Fed can continue to see inflation fall without entering into a period of layoffs or rising unemployment.

While it should be surprising that the Fed isn’t celebrating these recent inflation numbers, it is consistent with their official stances in recent months: No matter the sources of inflation over the past two years, the Fed believes that tight labor markets and high levels of nominal wage growth will keep inflation above their 2 percent target. The Fed has therefore set out to weaken the labor market to lower inflation, even if it risks a larger recession and millions of jobs lost.

But the evidence shows that such a harsh path is not necessary, and that inflation can weaken further even as the labor market remains strong.

With measures of labor demand cooling and key sectors catching up in supply, the Fed has a choice: They can allow for a wait-and-see period that lets a soft landing materialize, or they can insist that unemployment must go up to crush inflation, introducing the risk of a serious recession. Such a recession risk should not be taken lightly—as we saw in the aftermath of both the 2001 and 2007–2009 recessions, job recoveries can be very slow, with the majority of costs borne by low-wage workers, workers of color, and people on the margins of the labor force.

We think there are many reasons for optimism for a soft landing:

The labor market is already cooling without a rise in unemployment.

The labor market is set to cool even more, with wage growth continuing to decelerate.

This labor market is well suited to avoid employment declines.

The big “known unknowns” of 2023 all would surprise on the disinflationary side.

What the Fed Sees

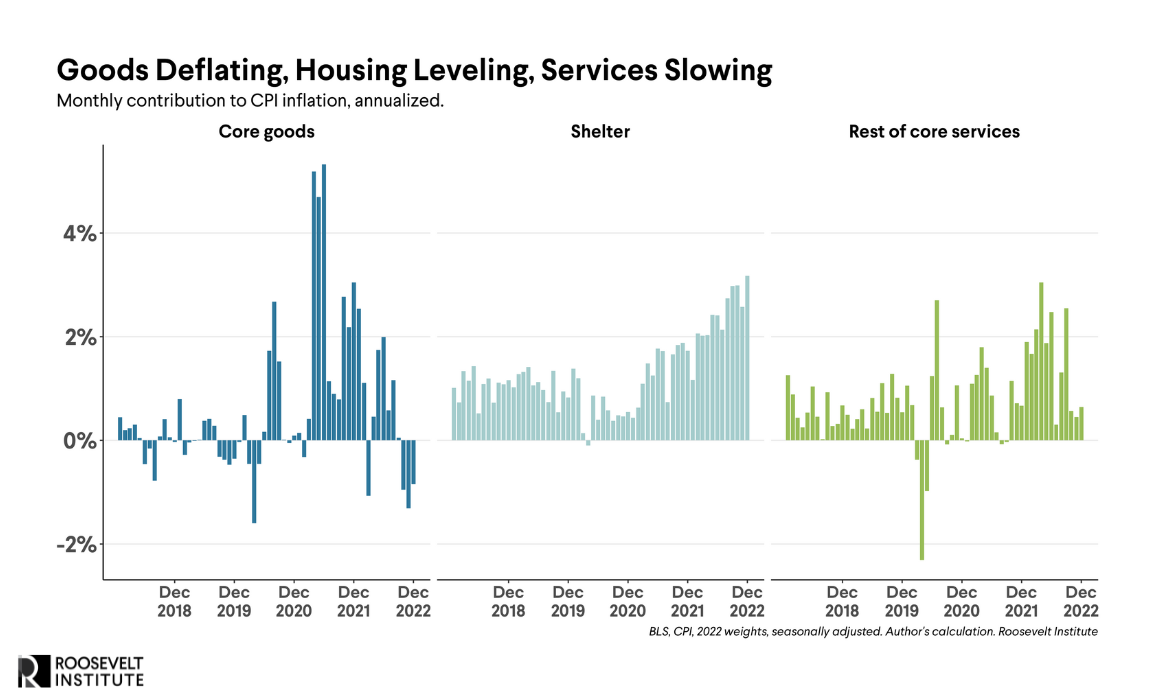

Officials such as Fed Chair Jay Powell and New York Fed President John Williams have said they are closely watching three categories: goods, housing, and the rest of services. (Housing is considered a service in the inflation data.) Goods, like cars and refrigerators, had seen zero or even negative inflation in the years running up to the pandemic. However, their prices skyrocketed over the past two years during reopenings, as consumers shifted their spending toward goods, and supply chains buckled under COVID. The Fed had, in the past, flagged that this would revert; as Chair Powell noted at Jackson Hole in 2021, “It seems unlikely that durables inflation will continue to contribute importantly over time to overall inflation.” As such, they are looking through the goods deflation of recent months.

They are also looking through the housing market, as it has likely peaked but won’t be reflected in the data for several more months. We see this through several pieces of evidence, including the recently released Tenant Repeat Rent Index (well summarized by Joseph Politano here) by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Their research finds that measured year-over-year inflation is peaking now and will begin to decrease in the middle of 2023.

So what are they looking at? Services outside of housing. As Chair Powell described it last November, the rest of services “is the largest of our three categories [and] may be the most important category for understanding the future evolution of core inflation. Because wages make up the largest cost in delivering these services, the labor market holds the key to understanding inflation in this category.” The challenge, as San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly described it, is that this category “has shown no sense that it’s coming down” and that historically, inflation there has “been persistent and very highly related to the progression of the labor market and wage growth.” In their view, unless they force the labor market to cool—which, in their latest projections, would cause unemployment to significantly rise—inflation won’t fully come down.

But, we are not actually seeing this kind of persistent inflation in services so far, as CPI inflation there has declined recently and largely tracked the reopening. Beyond that, we think this pessimism about the trajectory of inflation and the labor market is misguided for several reasons.

1. The labor market is already cooling without a rise in unemployment.

From the middle of 2021 through early 2022, the labor market was very hot. Wages were growing at around a 6–7 percent annualized rate, and vacancies and quits surged above pre-pandemic highs. These tight labor markets in the early days of the recovery led to substantial wage compression: Low-wage workers saw the fastest wage growth during 2021 and 2022.

During this period, there were various reasons why the economy was so strapped for labor. Many firms had laid off workers during COVID and needed to quickly rehire. The reshuffling of workers across firms meant that firms had many inexperienced workers who would take time to be productive, while workers had unprecedented ability to switch jobs for better pay. The recovery of demand was uneven across firms and sectors, and fast reallocation of workers across firms can contribute to faster wage growth. Many workers were still out of the labor force, as lingering concerns about health made the supply of workers in in-person service sectors much lower than was being demanded by consumers.

However, since the middle of 2022, wage growth has decidedly started to slow. The Employment Cost Index, the Atlanta Fed Wage Tracker, the Indeed Wage Tracker, and Average Hourly Earnings all show substantial deceleration in wages, despite many of these measures being substantially lagged. These measures also show that wage compression has slowed (the rate of wage growth for high- and low-income workers has converged), but as of now, there is no reversal: Low-wage workers are hanging on to their relative wage gains from the past two years.

Some of the slowdown in wage growth can be attributed to some reopening-specific factors receding. Firms are no longer rehiring their workforces from the COVID layoffs, and many workers have gradually rejoined the labor force. More durably, the amount of churn in the labor market has also decreased, with the rate of vacancies, hiring, and quits all down from their highs in early 2022.

Remarkably, wage growth and labor market churn have slowed as unemployment has remained consistently low. The unemployment rate has been between 3.5 and 3.7 percent since March of 2022, and initial unemployment insurance claims were more or less stable for most of 2022.

The fact that wage growth and churn have slowed without any noticeable increase in unemployment is remarkable and should be celebrated—many commentators have stated that any cooling in the labor market would necessarily mean a rise in unemployment. Even as nominal wage growth slows, a strong labor market that avoids rising unemployment also means that low-wage workers will hold onto their relative wage gains, sustaining the decrease in wage inequality we’ve seen in the last two years.

2. The labor market is set to cool even more, with wage growth continuing to decelerate.

The past few months of falling wage growth without increasing unemployment raise the question: Can this continue? We argue yes, as long as the Fed is patient. Current labor market indicators suggest that labor market tightness is cooling enough to lower wages further, but without making firms want to lay off workers. For example, weekly hours have dropped significantly, and employment in temporary help services has declined. Both of these series tend to be early indicators of firms’ hiring intentions and future demand for labor.

There are various other indicators that point toward further slowing in labor demand and worker churn: Continuing unemployment claims have returned to 2019 levels, the share of unemployed workers who left their job voluntarily (a sign of worker confidence) has peaked, the employment component of the Services Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) has weakened substantially, small business are reporting slowing hiring intentions, and workers are less sanguine about their outside options. All of these indicators point to a labor market where competition for workers will continue to gradually fall in intensity, likely signaling further deceleration in wage growth over 2023. Hopefully, however, none of these indicators is moving so drastically to suggest weakness or large future layoffs. Whether the labor market converges to “strong but cooler than 2022” or a recession is in the hands of the Fed.

Given that wages are still growing faster than the 3 percent rate seen before the pandemic, and given that labor market churn is still above 2019 levels, we believe that wage growth has room to fall, and continued moderation of labor demand will mostly affect wage growth rather than increasing unemployment.

3. This labor market is well suited to avoid employment declines.

Monetary policy does not affect all parts of the labor market equally. In particular, housing and durable goods manufacturing typically bear the brunt of job losses in response to higher interest rates. One plausible way that a soft-ish monetary tightening could play out is that the goods sector sheds workers, but the relatively unaffected service sector soaks them up, as happened in the “invisible recession” of 2015–2016.

But even this not-great-but-still-soft-ish scenario hasn’t come to pass. Instead, we have seen continued record employment in construction and post-2008 highs in manufacturing. In part, these booms reflect real structural shifts in the economy, including demand for more space for working from home, as well as re-shoring and domestic investment in manufacturing capacity.

This resilience also reflects temporary supply chain issues and chip shortages that generated significant backlogs in both home construction and auto production. The number of new private housing units under construction remains at a record high, and the cumulative deficit of car sales since the beginning of the pandemic is at least 6 million cars. With supply still far behind demand, employers have no reason to lay off workers. Accordingly, layoffs remain at record lows.

Given this unique circumstance, the Fed may be able to have its cake and eat it too: Labor market churn and wage growth are decelerating without any measurable increase in layoffs. If the Fed is waiting for unemployment to rise to be convinced of lower wage growth, the higher unemployment rate may not happen. Instead, it’s possible that all of the labor market cooling happens on the churn and wages side, and almost none on the layoffs side.

The risk is that the Fed doesn’t believe this is possible, unnecessarily throwing people out of work as wages were going to come down anyway. And as we’ve seen in past recessions, it is hard to control where the unemployment rate stops once it starts rising, and recoveries can be painfully slow.

4. The big “known unknowns” of 2023 all would surprise on the disinflationary side.

There’s a lot we don’t know about the economy’s path in 2023. But two things we know we don’t know are the extent to which corporate profits and business margins will compress, and whether we’ll see productivity increase. If either of these happen, there’s room for lower inflation given any level of nominal wages, and, in turn, patience in addressing inflation.

Right now, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow predicts 4.1 percent real GDP growth for the fourth quarter of 2022. Combined with slowing average weekly hours worked, this would mean an increase in measured productivity. Meanwhile there is some evidence in the financial press of corporate earnings declining and margins compressing. Furthermore, the labor share of income hasn’t increased in this recovery, so there is room for it to grow. As Josh Bivens of the Economic Policy Institute notes, historically the labor share often increases as a recovery goes on. Again, these are not predictions of what will happen. But to the extent things do happen here, the direction is toward disinflationary pressures that should inspire more patience at the Fed.

Conclusion

Inflation has come down dramatically in the past three months, exactly in line with what a soft landing would have predicted. This happened while the economy added over 700,000 jobs and the labor market remained healthy. All of the underlying trends suggest the Federal Reserve should be more patient in its approach to inflation and the labor market. Whether the labor market converges to one that is still strong and works for everyday people, or we instead face a recession, is in the hands of the Fed.